Anno Sjoerd Brandsma was born in Bolsward, the Netherlands, on 23 February 1881. His parents were Titus Brandsma and Tjitsje Postma, who were farmers and Catholics. Titus was one of six children. Five of his siblings entered religious life. Anno took his own father’s name, Titus, when he became a Carmelite. He was ordained in 1905.

Titus was drawn to join the Carmelites because of the Marian aspect of the Order as well as its prayer life and spirituality: “The spirituality of Carmel, which is a life of prayer and of tender devotion to Mary, brought me to the happy decision to embrace this life.’

During his student days Titus’ character was beginning to emerge. Prayer and fraternity were important to him but he also took the opportunity to read extensively and maintained an interest in wider culture and society. Titus also began to write for publication, developing his innate gifts as a religious writer and as a journalist with a passion for addressing a wide audience in an accessible way.

His Frisian heritage was very important to Titus, both its language and its culture. He did much to promote the cult of St Boniface, sometimes known as the ‘Apostle of Frisia’.

Titus was never physically robust and suffered ill health throughout his life but to those who knew him he demonstrated immense inner strength and something of the ‘determined determination’ his beloved St Teresa of Avila spoke about.

Titus was a gifted communicator. His articles in the Catholic press were aimed at a mass audience and were written in an accessible and inviting way. His lectures on Carmelite mysticism, delivered in the United States in 1935, are a true classic of twentieth-century spirituality.

A central conviction of Titus was that ‘God is the deepest ground of our being’ and that this is innate in our nature, in our brothers and sisters, and in the created world itself. In his thinking, Titus was informed by many spiritual writers from the Carmelite tradition, especially Teresa of Avila, and from the Dutch mystical tradition. This indwelling of God is not simply a personal thing, to be kept private. It should manifest itself in our lives, in our work, and in our relationships with others. For Titus, Mary was the prime example as one who interiorised the Word, let it shape her life, and gave it back to the world and to those who welcomed it as she did. Christians are, therefore, called to be ‘other Marys’ or ‘other God bearers’ in the world.

Titus was a serious academic and serious in his living out of the religious life. Those who knew him also attest to his sense of fun which is endearingly revealed in some of the photographs of Titus which survive.

Titus was known for his caring disposition towards his brothers but particularly towards the poor. There are eyewitness accounts of his giving away money, his overcoat, and even the blankets from his bed. Titus was known to assist an old man in pushing his junk wagon up the hill between the university and the Carmel, placing his professorial briefcase on top while he did it.

Titus was known as a ‘reconciling figure’ by those who knew him. Ecumenism came naturally to him together with an ability to break down barriers and enter dialogue. Titus, ecumenical spirit was acknowledged by many witnesses from other Christian denominations who spoke about him after his death. One protestant pastor said of him: ‘Our dear brother in Christ, Titus Brandsma, is a true ‘mystery of grace”.’

Titus was a peacemaker, but he also understood that this takes courage and that there are times that working for true and lasting peace, and thirsting for justice, will bring one into conflict with the world: ‘the one who wants to win the world for Christ must have the courage to come into conflict with it,’ is a famous statement of him.

Titus was a peacemaker, but he also understood that this takes courage and that there are times that working for true and lasting peace, and thirsting for justice, will bring one into conflict with the world: ‘the one who wants to win the world for Christ must have the courage to come into conflict with it,’ is a famous statement of him.

An example of Titus’ stand, based on Catholic principles and the rights of people, was his care for Jewish students. This brought him into direct conflict with the authorities. He refused to remain silent when Jewish students were excluded from attending Catholic schools. Titus even made enquiries about sending Jewish students to Carmelite communities and schools in Brazil.

Titus subjected National Socialism to rigorous critique as part of his university courses and was especially vocal against Nazi ideology in a number of his sermons. After the invasion of The Netherlands, Titus and others intervened to stop Nazi propaganda being printed and disseminated. This brought him to the attention of the authorities and led to his eventual arrest.

Titus was arrested on January 19, 1942. His journey to Dachau was arduous and difficult. He was moved through a number of prisons and camps before arriving at his final destination.

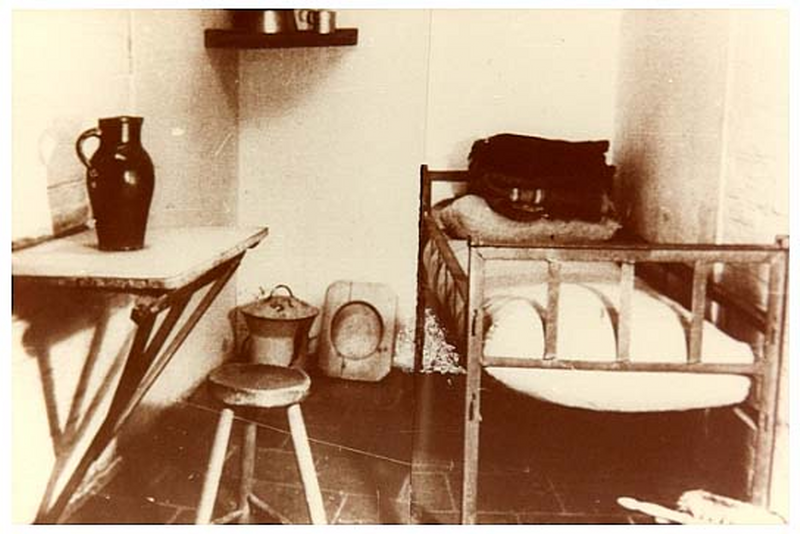

In his cell at Scheveningen Prision, even in the ‘cold and chill’ Titus discovered anew the benefits of solitude. Unable to receive the Eucharist in person he made daily acts of spiritual communion, sometimes singing the Latin Eucharistic hymn (words by St Thomas Aquinas), Adoro te devotee to himself.

During the COVID-19 pandemic many have learned to make an act of spiritual communion.

Titus had before him in his cell at Scheveningen a picture of Christ Crucified by Fra Angelico. For Titus, the act of looking at the image of Jesus in his cell is not one-sided. It is based in friendship. It is a look that is returned. From the Beloved to the one loved. A gaze that travels back and forth in mutual understanding, support and love.

As Titus puts it in the poem he writes:

O Jesus, when I look on you, My love for you starts up anew,

And tells me that your heart loves me,

Any you my special friend would be.’

Titus was always interested in the theology of the Cross. Apart from his famous poem written in front of an image of Christ crucified, he penned sets of meditations on the Stations of the Cross. This seemed to prepare him for what was to come. He even forgave his captors, following in the steps of Jesus.

At Dachau, Titus became for many of his fellow prisoners a light in a dark place. He was a source of hope and comfort to his fellow inmates who gravitated to him, often gathering around his bed.

At Dachau, Titus became for many of his fellow prisoners a light in a dark place. He was a source of hope and comfort to his fellow inmates who gravitated to him, often gathering around his bed.

Titus was killed by lethal injection on 26 July 1942. He died close to two o’clock in the afternoon. He was 61 years of age. In 1942 alone some 800 clergy died at Dachau.

There is the well-documented story of how Titus gave his Rosary to the woman who administered his injection and encouraged her to use it even though she had forgotten how to pray. Later she attributed her return to the faith to the intercession of Titus. As part of her testimony during the process of beatification, she affirmed that Titus’ last words, ‘Let you will, not mine, be done, O Lord,’ made an enormous impression on her.

St Mary Magdalene di Pazzi rang the bells of her convent in Florence to announce that love is alive and beautiful. Titus too is that clear, bell-like voice, that speaks across time and place, and announces that the love of God is alive, even in very challenging times and places, and that the love of God makes all things new and brings beauty to our world. Titus demonstrates, as Christians always have, that Love triumphs over evil.

From his poem:

For, Jesus you are at my side;

Never so close did we abide. Stay with me Jesus, my delight,

Your presence makes all things right.

Titus was beatified by Pope Saint John Paul II on November 3, 1985. We continue to pray for his canonisation, encouraged by the recent approval, by both the medical experts and the theologians, of a miracle attributed to Blessed Titus’ intercession.

SN

Download the pdf Liturgy for today.